In the discussion of encouraging young adult males to read more

is there a more effective method than Spoken Word?

Spoken Word

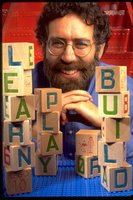

I Was Born with Two Tongues. Dennis Kim (with baseball cap), Anida Esguerra, Darius Savage (bass player), and Marlon Esguerra perform at the Locus Arts Space in San Francisco. Photos by David Huang.

Slam POETS mix words and music and mojo and intellect into POLITICAL performance ART

By Neela Banerjee

Spoken word poet Dennis Kim lets loose with a barrage of words about his Korean American identity to the hard-strumming of Darius Savage’s upright bass in Japantown’s Locus Arts space. For this recent sold-out performance, the room’s booths are packed and poetry aficionados spill onto the floor, bopping their heads to Kim’s words:

“The hungry scent of sorrow on the skin of my people, Han. The muddy face of my unborn children. Han. My crooked foot searching for the footprints of my grandfather. My Han.”

Kim’s face contorts into a grimace of concentration as the words spill from his gut, his right hand twists the bill of his baseball cap back and forth to the rhythm of his song, his left index finger points toward the mirrored ceiling to emphasize his story, and one foot taps just off the ground. Suddenly, Kim breaks into Korean folk singing, his voice deep and sorrowful, catching the audience off-guard. But the rhythm continues and he flows back into English. The bass gets jazzy and the audience goes wild.

Kim, along with Marlon Esguerra, Anida Esguerra and Emily Chang, make up the Chicago-based pan-Asian spoken word poetry group known as I Was Born with Two Tongues. Since their inception in 1998, Two Tongues have been touring nationally and representing Asian American talent on the spoken word scene.

The Eighth Wonder poetry collective. Back row, left to right: Isagani “Starr” Pugao, Jason “Kreative Dwella” Mateo, Alan “Quest” Maramag, Jeremy “Kilusan” Bautista. Front row: Lillian “Dirty Dot” Prijoles, Irene “Shorty Rocwell” Duller, Jocelyn “Hi-Five” DeLeon, Golda “Supanova” Sargento. Photo courtesy of Eighth Wonder.

Voice of a Generation

With its blend of hip-hop stylistics, political empowerment, anger and beauty, spoken word has become a voice for America’s youth, activists, and those typically seen as voiceless. Spoken word, at its simplest, is nothing more than the oral tradition of poetry. But in the coffeehouses and bars across the country, where poets step up to microphones to speak memorized verses of personal truths, this scene becomes the nexus of art, activism and culture for an entire generation.

Young Asian American poets have been making a serious name for themselves in this scene, from Chicago’s Two Tongues to the Bay Area’s own Eighth Wonder collective. Bringing the diverse struggles of Asian Americans to the forefront, these artists continue the tradition of blowing the doors open and creating art that is based in the community.

The spoken word movement dates back to just 10 years ago. Since then, poetry slams — where performers are scored by audience members on a scale of 1 to 10 based on their overall performance, stage presence and style — can be found in even the smallest American heartland towns. Most devotees of the art form credit Marc Smith, who ran competitions out of Chicago’s Green Mill, for the creation of the modern slam.

The roots of the slam concept originate from the ancient culture of competitive or linked rhymes. These traditions can be traced to Grecian intellectual poetry, African griots, Japanese and Islamic courtly poetry contests and Filipino political debating. The slam also was heavily influenced by hip-hop culture’s talent battles, with DJs, emcees, break-dancers and beat-boxers often involved in friendly rivalry.

In January, Kim and Beau Sia were featured guests at Second Sundays, a monthly poetry slam at San Francisco’s Justice League. Second Sundays, with an average of 500 attendees per show, is rumored to be the largest slam event in the country and showcases some of the most renowned poets in the nation, including slam champions such as Sia. Displaying his unique style, Sia often starts his performance with a break dance, then lets loose a poem focusing on emasculating myths about Asian American males.

Nearing midnight, the Second Sunday show climaxes when he and Kim take to the stage. Sia’s poetry morphs into an in-your-face tribute to Asian America, as he sings out the names of Asian ethnic groups.

Not missing any of the API contingents, he then belligerently calls out, “Doesn’t it feel great to be Asian American right now?”

At that moment, it seems Sia has empowered every Asian American in that room.

Celebrating Heritage

I Was Born with Two Tongues. Left to right, Darius Savage, Marion Esguerra, Dennis Kim, Anida Esguerra. (not pictured: Emily Chang). Photo by Neela Banerjee.

The Two Tongues crew performs at a lunchtime concert series in celebration of Asian Pacific Heritage month at DeAnza College. On a makeshift stage in the center of campus, Anida Esguerra performs her piece about comfort women. Around 50 to 60 Asian American students crowd onto tables and benches, under the shade of trees. Further out, others play hackey-sack, pore over books and eat cafeteria food. A white male student walks by, sees a friend and stops to listen. His blond hair is tousled as he removes his white hat. He unloads his heavy backpack and sits down on a bench. Esguerra’s voice is loud as she cries out in detail about the rape of women. It is only a matter of moments before the student reaches for his backpack and hurries away. After the show, both Esguerras (Anida and Marlon are married) and Kim sign autographs, take pictures and have intense conversations with students.

The DeAnza show comes after the Tongues spent an entire day at Newark High School, where they did six performances in a row. They are exhausted but the energy they exude seems endless. Over and over, Asian American women approach the poets to say that the first time they heard a Two Tongues poem, they were moved to tears. The Tongues give out hugs as freely as they give out encouragement. They tell people to send them poetry. They listen to stories about the state of race relations at DeAnza, and make small talk about the importance of eating dessert as a first course.

After half-an-hour, Kim finally sits under a tree while students continue to approach him. His sincerity and energy make him seem other-worldly and familiar all at once. The other poets join him and shed light on their genesis.

Kim and Marlon Esguerra met in Chicago in the mid-1990s. They both frequented the predominantly African American open-mic scene, and naturally gravitated toward each other.

“When we saw each other, it was just this sort of magical experience,” Esguerra says.

Kim and Esguerra began performing together more and more in Chicago. The members of the group attended a meeting called by the Seattle-based Filipino arts collective known as Isangmahal, which in Tagalog means “one love.” Isangmahal’s art includes poetry, hip-hop, dance, percussion, native Filipino instruments and mixing. Seeing the importance of collective creativity inspired the soon-to-be Tongues to form their own group.

Soon after, Kim was offered the chance to headline a show at Chicago’s poetry spot, The Mad Bar. But he had a larger vision and wanted to bring others on board with him for what was supposed to be a one-night show.

“People really responded,” Anida Esguerra says. “There was a real need for it, an urgency.”

Kim came up with the name I Was Born with Two Tongues, which really captures the pan-Asian aspect of the group. Marlon is a second-generation Filipino American, who works as a teacher and helps out with his wife’s business. Anida identifies as Cambodian Malaysian Muslim American and runs her own graphic design firm in Chicago, Atomic Kitchen Design. Chinese-Taiwanese American Chang, who lives in New York City, works as an editor in a social science publishing foundation. Kim, who is Korean American, not only tours with Tongues but is also part of the hip-hop group Typical Cats.

“When I first started reading, it was just to get my feelings out,” Marlon says. “It was a lot of pent-up frustration and anger. It was basic.”

ünida says she began writing because her soul was crying out to create. Coming from a visual arts background in college, she was looking for an inexpensive alternative to express herself, and picked up a pen. She had never tried writing poetry before.

“When I started this, I couldn’t go up there alone. I was scared,” Anida says. “But this is my family right here. This is how I am able to go up there. Because of our growth together and our support of each other, it keeps us going.”

Kim talks about his poetry as necessity for his existence.

“I know I did it to be seen and heard, to exist on my own terms,” Kim says. “It was incredibly, crucially important to me. It was horrifically important to me at that time. A matter of survival, in a sense.”

Since the Tongues exploded onto the scene, many more Asian Americans have been visible. Nowadays, Marlon says, it is not uncommon to see two or three Asian Americans at open-mics in Chicago.

“I don’t think there was this thing, that the Tongues came and suddenly there was Asian American spoken word,” Marlon says. “I think we were a fresh voice. Our voice was deeply integrated and inspired by poets, spoken word artists, political figures and movements.”

When asked to define spoken word, the poets balk. They give simple definitions along with complex ones, along with refusing to pin down the concept.

“It’s just a word, just a term and it’s useful to a certain point, like the term Asian American or hip-hop,” Kim says. “I know the essence of it and that is where our lives are intimately caught up. It is the Korean folk song tradition, which is a sort of improvisational public mourning. As Marlon says, it’s our ancestors wearing the hides of animals sitting around a fire yelling at each other at the end of a day. It is also Janice Mirakatani and Garrett Hongo and Nabuko Miyamoto.”

Most of Two Tongues’ poems are identity-based and deal with issues such as class, racism, misogyny and exoticization. Anger toward American systems fuels the energy of their words. Before Anida performs the poem Excuse Me, America, Marlon and Kim step onto the stage and with biting monologues, transform themselves into caricatures of their spectators. Kim speaks in the voice of a stoned college student, a thugged-out Asian, and even Anida’s mother — all asking, “Why is Anida so angry?”

“I think people underestimate the power of art as activism,” Anida says. “We are political poetry. We are just telling the shit we feel and telling our stories. Actively participating in trying to create a better world and trying to create change, which starts within yourself.”

Says Kim: “If I’m going to get down with the revolution, I’m not going to get down with one that is soulless. I think what we are doing is revolutionary … It is the belief in, and the enlargement of, and the defense of, and the creation of something beautiful and powerful that can sustain us … It is our families, our babies, it is being able to sit under a tree and talk to a friend.”

Meant to be heard, spoken word has yet to earn respect on the page. In academic settings, professors often reject the poets’ spare, rhyming works.

But San Francisco State University ethnic studies professor Allyson Tintiangco-Cubales is working to change that. Utilizing the energy of spoken word, she hopes to inspire her students. This past year, Tintiangco taught a new course entitled “P/Filipina/o American Pinay/Pinoy Literature.” Tintiangco wanted her students to create ways to make the literature available to people outside the classroom.

The students surpassed her expectations. In both the fall and spring semesters, they created a CD, a zine and a Web site to showcase their work — much of which was spoken word poetry. And as final projects, both classes held performances that attracted over a hunded people.

“Students really like spoken word, and if you can get them interested in literature through spoken word, why not do so?” Tintiangco asks.

In legitimizing spoken word, Tintiangco is blazing new paths. Practically no academic writing exists on this form of poetry. Tintiangco pushes her students to understand the connections between spoken word and activism, but she wants them to move past that, as well.

“Spoken word is definitely a form of activism but it is not enough by itself,” she says. “When I start talking to my students about spoken word, I say this is not just it. If you are going to go out there and voice all these things, you have to do things that will make a difference, also.”

Tintiangco also encourages her students to respect a diversity of literature, which is important to her as a poet and author who writes across genres.

“Someone asked me once if I think spoken word is the best kind of poetry, and I replied that that was an ignorant question,” Tintiangco says, laughing. “I feel that a lot of folks in our community don’t read a lot, and our writing depends on what we read. The change I see in my students’ writing from the beginning of the semester to the end is amazing, and I think it is due to the reading that they do.”

Tintiangco, who is recognized as a major inspiration to many younger spoken word artists today, emphasizes the importance of understanding spoken word as part of a larger legacy, not only going back in tradition but also in Asian American history.

“Since the Third World Strike at Berkeley, people were doing spoken word and poetry,” she says. “Maybe it wasn’t called spoken word, but people were going out there and reciting their stuff. I mean, we wouldn’t even be able to speak out loud if it wasn’t for the Third World Strike.

“I think it is important to look beyond that, too. Silence was something that was forced upon us but we were never really silent. Sometimes we get caught up in thinking we were silenced, but we didn’t ever really accept it. Asian Americans were always writing and talking and yelling out loud.”

San Francisco’s traditions of beat poetry and Asian American empowerment set the stage for the birth of a local poetry collective known as Eighth Wonder. Less than a year old, the four-man, four-woman Filipino American group creates ripples that are reaching halfway across the nation and far into the cosmos.

Like the Two Tongues, Eighth Wonder was brought together by another young, prophetic poet named Jason Mateo. Like Kim, Mateo’s stage presence is nearly triple his actual size. (He stands just barely 5-foot-4.) His spoken word, beat-boxing and freestyle skills have earned him god-like status on the local scene.

In July of 2000, Mateo was asked to open for the Two Tongues at a performance they were doing at Bindlestiff Studios, a San Francisco-based center for Filipino performing arts. The vision for Eighth Wonder appeared before Mateo as he looked out at the eight tiers of seating around the stage at Bindlestiff, which to him, looked like rice terraces.

“For years the rice terraces in the Philippines have been considered the unofficial eighth wonder of the world,” Mateo explains, at an intense discussion with four of his fellow Wonders. “I wanted to bring that concept, the number eight in its infinite possibilities, to life.”

Mateo’s dream was to bring together a group of four men and four women poets, all Filipino, to open the Tongues’ show. From there, he pulled this crew together. All the members were involved in the community, where Mateo had either witnessed or heard about their skills and creativity. Mateo rounded up the spoken word artists from across the Bay Area, from Vallejo to Santa Cruz: Lillian “Dirty Dot” Prijoles, Irene “Shorty Rocwell” Duller, Golda “Supanova” Sargento, Jocelyn “Hi-Five” DeLeon, Jeremy “Kilusan” Bautista, Isagani “Starr” Pugao, Alan “Quest” Maramag and Jason “Kreative Dwella” Mateo. All of them are under 25.

The first time they gathered in a room together was also the day of the Bindlestiff show. The energy was impossible to ignore, they say. From that day on, Eighth Wonder has been together, performing in San Francisco, Los Angeles and Chicago.

In 1996, Mateo was indoctrinated into the world of spoken word with the genesis of the literary arts nonprofit known as Youth Speaks. The organization is largely responsible for getting the youth slam scene started, and is the beneficiary of funds from Second Sundays events.

Other Wonders shared their stories: Duller, who recently moved to the Bay Area from Los Angeles, says she “grew up as a loyal hip-hop follower, a citizen of the hip-hop nation. Add that to talk-story in the living room, and the actual articulation was in 1996.” Originally from San Diego, Prijoles, a film student at the Academy of Art, says she was always writing and reading, and started participating in the open-mic scene in the last few years. Prijoles began hosting open-mic events at her house, which attracted large crowds and created a real community. Bautista, a student at U.C. Santa Cruz, says he was going through some tough times in high school, when a teacher encouraged him to write.

“If my teacher did not tell me to write and put my feelings down, I would have just been another statistic,” Bautista says solemnly. He continues on in a soft-spoken voice to talk about the importance of word to him, with the peace and serenity of an ancient wise man. As he explains, the other poets nod their heads and call out affirmations.

“I believe in using the word as a device to speak your truth and understand what you are going through … Sometimes when it gets too clogged in your head … the word is a way to express all this chaos and allows the art to quantify and beautify it, “ Bautista says. “Eighth Wonder is a sanctuary, in my opinion, because we are all finding refuge in the word.”

For Eighth Wonder, spoken word is also a nebulous form. For Duller, it is freedom. For Prijoles, it is voicing her perspectives.

“Our ears are affected by mainstream media, street bullshit, chismis [gossip], oppression, institutions that discriminate against us, the workplace,” Mateo says. “Our ears are already affected in so many ways that it is important for spoken word to be there, to be that nurturing syllable for the ear, the mind, the soul.

“The importance for spoken word in my life is a poem in itself. I found a sense of identity at the age of 17. I found a sense of being Filipino American, knowing about my roots. Spoken word has been a teacher and a pillow and an inspiration that has started my creativity dwelling in this urban city.”

As a Filipino American collective, the Eighth Wonder poets say they don’t intend to always focus on poems about identity. At times, their work is more of a response to the system.

Says Bautista: “We are living in a cut-throat society. Corporations are absorbing the resources that should be for the people. Spoken word provides an alternative to that machinery. It is not a truth or the light, not a negative or positive, but an alternative… Who is to say what I am saying is the truth? It is just another perspective. But because there are many degrading representations of Asian Americans in the mainstream media, this gives us a chance to represent our people, our people’s struggles.”

The other poets agree, citing their work as something more than just an art or entertainment, but something that is inherently intertwined with their community, family and heritage. Mateo, at one point, almost echoes Dennis Kim’s words verbatim, saying “This movement is so important. This is necessary.”

Duller, too, identifies the Eighth Wonder members not as politicians or poets, but as revolutionaries.

“What Eight Wonder encompasses is revolution,” Duller says. “And in that term I don’t just mean in a political context. Revolution is love, feeling, change, education.”

Looking ahead, Eighth Wonder hopes to grow and learn, both together and individually. All members hope to use their work and teach in the community, bringing people into the glory of spoken word and its powers. Mateo plans to work with teens this summer at the West Bay Filipino Community Development Center, and also has plans for the young collective.

“I want to make such a strong movement that it is in your face, like NoLimit Soldiers,” Mateo says earnestly. “Not to sell out but to get in the faces, into the masses and let folks feel the movement, not even necessarily Filipino American, but our larger community. I want to see an Eighth Wonder spoken word video on BET.”

The poets chuckle over this, but then sit back and think about it.

Duller adds: “I think it is time that normal, down-to-earth, down-home folks become heroes.”